History & Modern practice of the Enharmonic Genus. Part 1.

Jean-Philippe Rameau

Rameau provides us with much in a single paragraph. However, we shall need only two sentences to provide us with the necessary impetus to begin our discussion. And as such they are worth repeating;

“In the use of melody, it seems that the Ancients surpassed us, if we may believe what they say. Of this one it is claimed that his melody made Ulysses weep; that one obliged Alexander to take up arms; another made a furious youth soft and human”

Rameau, Jean-Philippe.

There are many way in which ‘the Ancients’ may have surpassed those who came later and I suggest that one may be the general use of the enharmonic genus.

Austere and Majestic.

A certain Father Martini (Levin 1961) informs us that “they [the ancient Greeks] used the diatonic to express and move serious, robust, and firm affects and the chromatic to stimulate soft, suggestive, and sentimental affects. The enharmonic, by itself, was austere and suited to express majesty and decorum.”

| Genus | Martini Affect | Largest Interval in Tetrachord |

| 1. Enharmonic | austere, majesty and decorum | major 3rd |

| 2. Chromatic | soft, suggestive, and sentimental affects | minor 3rd |

| 3. Diatonic | serious, robust, and firm affects | major 2nd |

Table 1. -The Enharmonic, Chromatic and Diatonic-

To achieve the enharmonic major 3rd within the tetrachord the 1st tone above the fundamental tone must be intoned at some fraction of a minor 2nd – namely a ‘quarter tone’. Hence, the enharmonic is characterized by a fundamental tone – a quarter tone – a quarter tone – and a major 3rd to complete the tetrachord at the 4th above the fundamental.

It is easier on some instruments than others to achieve the enharmonic effect – fretless instruments and instruments with reliably bendable strings are suitable. The electric guitar is suitable for enharmonic performance in various keys and positions.

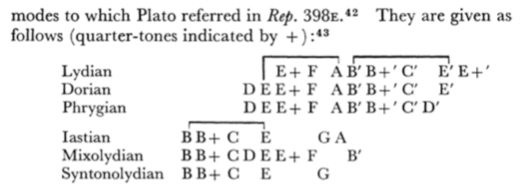

Before moving to the guitar we should turn to Plato’s Republic and decide which enharmonic scales we should examine, perform and compare.

“What, then,[398e] are the dirge-like modes of music? Tell me, for you are a musician.” “The mixed Lydian,” he said, “and the tense or higher Lydian, and similar modes.” “These, then,” said I, “we must do away with. For they are useless even to women who are to make the best of themselves, let alone to men.” “Assuredly.” “But again, drunkenness is a thing most unbefitting guardians, and so is softness and sloth.” “Yes.” “What, then, are the soft and convivial modes?” “There are certain Ionian and also Lydian modes[399a] that are called lax.” “Will you make any use of them for warriors?” “None at all,” he said; “but it would seem that you have left the Dorian and the Phrygian.” “I don’t know the musical modes,” I said, “but leave us that mode that would fittingly imitate the utterances and the accents of a brave man who is engaged in warfare or in any enforced business, and who, when he has failed, either meeting wounds or death or having fallen into some other mishap,” (Plato 398e-399a).

Plato’s Republic

So, Plato recommends the Dorian and Phrygian modes – seemingly, with a preference for “that mode” the Dorian. Luckily there is a reference from Aristides Quintilianus (Levin 1961) that gives us a spelling for the 6 modes mentioned in The Republic. Quintilianus includes the Dorian and Phrygian as they were before being reordered by Pope Gregory the Great (A.D. 590-604) as he reformed a subset of plainchant into what we know as Gregorian chants (Helmholtz 239). As a part of this reordering the names of the Dorian and Phrygian modes were swapped. See Table 2.

| Quintilianus | Platonic | Modern Diatonic Modes |

| Lydian | Tense Lydian | Lydian |

| Dorian | Dorian | Phrygian |

| Phrygian | Phrygian | Dorian |

| Iastian | Ionian | Ionian (Major} |

| Mixolydian | Mixed Lydian | Mixolydian |

| Syntonolydian | Lax Lydian | Locrian |

Table 2. -Comparison of Terminology. The modern Aeolian and ancient equivalents are not present.-

Plato’s Enharmonic Dorian and Phrygian Modes.

And now we have two candidates for a melodic approach that may be “austere and suited to express majesty and decorum.” As well as “fittingly imitate the utterances and the accents of a brave man who is engaged in warfare or in any enforced business, and who, when he has failed, either meeting wounds or death or having fallen into some other mishap.”

Before moving onto some applications on the guitar it’s worth mentioning that Doria is an area in the south of the Peloponnese Peninsula that is historically most associated with Sparta. Phrygia is located in modern Turkey and is historically, among other things, associated with Troy.

Finally, before finishing, I will give the spellings of the Enharmonic Dorian and Phrygian Modes that I will explore in the next post. Using the nomenclature set forth by Levin (1961) I will show quarter tones with the sign +.

I will set the fundamental tone as A = 440hz and I will give all examples the same fundamental note so as to allow direct comparison.

Dorian = A A+ Bb D E E+ F (A)

Phrygian = A B B+ C E F# F#+ G (A)

REFERENCES

Helmholtz, Hermann. On the Sensations of Tone. Dover Publications. 1954.

Levin, Flora R. “The Hendecachord of Ion of Chios”. Transactions and Proceedings of the American Philological Association, Vol. 92 (1961), pp. 295-307. The Johns Hopkins University Press.

Plato. Plato’s The Republic. New York Books, Inc., 1943.

Rameau, Jean-Philippe. Treatise On Harmony. Dover Publications, 1971.

Leave a comment